This is a selection of text fragments from my research projects: including work on the history of photography and the theoretical questions it raises for all forms of art practice; a manifesto I wrote for my students when running the UAL Foundation Diploma in Art & Design at Suffolk New College, UK; a poetic text from a body of work Ghost; an article about objects and memory for a UK project; a review of a Tate conference on colonial film archives; a rationale for the body of work Archive Fever; and a paper based in my Doctoral research.

Photography contra sublime: is there still ‘the sublime’?

Published in the Edgar Wind Journal, University of Oxford, 2013

If the sublime requires a conceptual mastery of the experience of terror/awe when confronted with the image, how then might we understand the operation of the sublime through the image that replaces the memory of the event?

We rely on the indexicality of photography and assume, even while aware of the ease with which we manipulate the digital image, that there remains a functional representational value to the photographic document. At the same time we conveniently forget Barthes notion of the photograph supplanting the memory it represents . Barthes was describing the portrait of the face of the beloved in the first instance, but extrapolated his theory of photography and memory from that analysis. If this aura of photography still holds and can be expanded to include cultural not just personal images; and if the sublime can still be experienced through representation; then at the intersection of cultural memory & the image lies a complex process of displacement. So much so that historical images come to stand in for the trauma they document, and simultaneously cover over their complex cultural meanings. This order of representation – the historical, perhaps cultural – sublime, allows us to master our terror, but simultaneously, by its continued circulation, to experience an unbearable forgetting. The images become a collective stand in that allows us to master the horror for which they are the mnemonic.

If we consider the photographic image of the Hiroshima or Nagasaki A-bomb cloud; or the films from the liberation of the concentration camps amongst several others of the same order, they become through their cultural saturation a kind of shorthand for far more complex and far more frightening histories because we prioritise the experience of mastery: it makes history bearable.

The constant televisual projection of the twin towers falling is of another order I think, and the marker of a change in era. Its relentless transmission means it has entered a Western, perhaps global, domain alongside the historical sublime. This order of photography and its intensity constructs images through which we as a culture attempt to master not just our terror, but our individual and collective powerlessness, and not through an experience of the sublime, but through the replacing of the memory of the event with an image.

In this compulsion to repeat, actually or symbolically, we are served by ever more efficient 24 hour digital flows of images and information: as Wark has argued these flows are not the same in all times & places, and this in turn privileges and silences, exposes and hides, just as previous forms of information circulation have done.

This sleight of hand creates a politicised hierarchy of images: and therefore a hierarchy of terror. Systems of representation, and transmission; and our consumption of images and media, mean we cannot but collude in this hierarchical structuring; attempting to keep those that are unbearable at arms length, and adjudicating their meaning in the process. It is no coincidence that this intense visuality of the event comes about at the same time as a turn in the nature of politics, whether conventional politics of the governmental kind, or the politics of representation in all its forms.

See Barthes, R Camera Lucida trans Howard, R Vintage Books London 1981/2000

See Doane, M A ‘Lost and Found Footage: The Historical Sublime’ presentation at ‘Out of the archive: artists, images & history’ Tate Modern November 18 & 19 2011

See Wark, M Telesthesia: Communication, Culture & Class Polity Press 2012

This précis is part of a much larger project on art & politics, and the end of postmodernity.

The Creative Act: a manifesto (for young artists)

UAL Foundation Art & Design Manifesto, SNC 2012

Art happens: no hovel is safe from it, no Prince may depend upon it, the vastest intelligence cannot bring it about, and puny efforts to make it universal end in quaint comedy, and coarse farce

Whistler

Creativity gets a bad rap. It makes a lot of contemporary Westerners nervous. It might look crazy. It may not pay the rent. It is considered either frivolous, providing the decoration for the important stuff in life; or not economically viable, showing no use value, no guaranteed return. It hardly even rates as history a lot of the time.It’s unquantifiable, yet you know it when you see it; it’s impossible to commodify, yet it’s invaluable; without it we would lack not just art, music & literature, but science, architecture, communication itself, those things that define us as human. It’s a term used to insult people whose primary job is to produce knowledge of the world, the more specific the better. It is in fact only the most essential force on the planet. It is invariably a solution to a problem; whether that problem is a 200 story building, or a story to engage young children. It will be the answer to global warming. And for each creative question, there are as many solutions as there are artists who strive to come up with an answer.

Ghost III

Ghost II UWS Sculpture Award & Exhibition, University of Western Sydney 2014

In the dark, in the stillness, in the silence/In the baking heat, the bitter cold, the crashing sea/In the still grey depths of solitude, a single breath is when you’ll find me.

‘La memoire est un sentinelle qui s’endort tout le temps’

The Memory Project collection edited by Annabel Dover London UK 2011

I work with things and their history, their semiotic charge, the way meaning inheres in their very materiality and symbolism. Yet I have had to let go of so many in order to live so far from home.

I gave them away, threw them away, put them in boxes in attics and cupboards. None of them matter any longer, like batteries that have gone flat, my investment in them is lost. And its only by doing without them that you realise they were nowhere near as important or precious as you thought.

What do you choose to take with you when you move 12,000 miles? I can only say: ridiculous things, unnecessary things, I could narrate the selection I no longer understand, my regret for things I’ve missed at times but no longer need, my desensitisation because I have had to draw myself out of all those objects that defined me and my sense of place.

But there is no explanation for why this thing at this time stands in for a little piece of identity or history or narrative, through which I define myself. Little anchors, it seems childlike to believe in them, my grandmother’s necklace, my grandfather’s ring, its stone missing, a cross-section of books to remind me of another time and place, and who I was then. There is more emotional content in picking up a much loved, much read book in a bookshop and thinking: I have a copy of this at home. Even if I haven’t seen it for years.

All I can tell you is that it doesn’t work: the anchors, the guarantees, the little things that Barthes would say supplant the memories you thought they represented, its all fiction and it all changes. Whether you leave home or not, to go to work, or to move countries, one day you wake up and nothing is the same as yesterday, and yes it’s like falling in love – and falling out of love – unexpected, unpredictable, excruciating. And the objects? Are no longer a comfort.

There is a space created when you pack things in storage: and in that space is not memory and intensity, but forgetting. And grief.

Out of the Archive: Artists, Images and History

Friday 18 November 2011, 10.30–17.30

Saturday 19 November 2011, 10.30–17.30

In collaboration with the London Consortium. This conference was originally conceived by the Colonial Film project team, and coincides with the launch of the Colonial Film: Moving Images of the British Empire website.

I believe it was Jane Elliott who once toured America saying that white people know as much about racism as black people: and that ignorance is first a privilege and then a choice. This is certainly what sprang to mind over the two days of this conference, which seemed to have a series of absences and elisions at its heart: absences and elisions to do with audiences and cultural ownership, and to do with the protocols of archives themselves, and their meta data.

May Ann Doane, reliably rigorous in her reading of selected films, and relating her response to the colonial film archive to her research on the historical sublime, made the point through example that the colonial film makers felt no need to identify or differentiate the individuals filmed. She suggested that the narrative voice over was part of the dehumanisation process, whereby one African bushman could be substituted for another without explanation.

Yet it seemed to me that this is exactly what Filipa Cesar had done in Black balance, by taking archival footage and cutting together a range of clips of different African nations and cultures in order to make clear – to emphasise – the racism of the white colonial film makers.

This seems to me to exemplify the problematic at the core of this publishing of the archive, and of any discourse around it. When questioned about the content and the audiences for this material, Frances Gooding suggested that there are many people ignorant of the Empire’s history, and that this archive will serve as a source of historical knowledge. What this fails to address however, is the questionable politics of remobilising these images with only that imperative in mind.

First, because it ignores what I would suggest is a considerable population sufficiently visually literate to read back the racism of the original. Secondly because it makes absent the viewpoint of people from the cultures represented (in the historical moment of those cultures dispossession), either as a primary text or in its remobilisation by the artist.

In this way, it seemed to me that much of the conference ran the risk of re-presentation without sufficient critique, and without imagining what it might be like to be viewing this material not as the coloniser, but as the colonised.

Surely we have an ethical obligation to return these images to the peoples whose history they document?

By way of comparison, there has been an Australian exhibition called In living memory which has attempted to deal with precisely these issues of cultural ownership.

“In Living Memory is a powerful exhibition of archival photographs from the NSW Aborigines Welfare Board taken between 1919 and 1966, combined with contemporary images of Elders, families and communities by senior Indigenous photographer Mervyn Bishop. In Living Memory first opened in September 2006 and proved to be so important to NSW Aboriginal people, international visitors and the wider community that is still remains open at State Records Gallery.”[1]

Some of the protocols for the making public of these images included consultation with those photographed, their families and their communities. No image was published without the express permission of the people represented or their families. So this archive, whilst a document to the assimilationist policies that destroyed so many Aboriginal lives, became an exhibition that returned in some measure a sense of history and representation to those whose lives they picture. The photographs were remobilised in a way that didn’t only refigure the history, but allowed people to reclaim personal and community histories and represent them in the present, via public discourse authored by those communities, and by a photographer who is a member of those communities.

In this way the project became much bigger than a white masculinist paternalist discourse about the mess we’re in: it became an effective and expansive political project concerned with cultural ownership and a dialogue between communities.

What I can’t help but wonder is: what protocols are in place for the use of material in these archives; and in the effective, if partial, doubling of the archive that this online resource represents? How are they being made available to the communities from which the images were taken? Relying on the idea that the internet makes these images available to everybody is naïve in the extreme, and I would hope artists and researchers from the colonised nations represented would have privileged access to this material. Or perhaps even be consulted about its publication; of images which represent not just the point of view of Empire, but, as film and photography cannot help but do, represent something about these cultures and their history.

Because wherever those questions are being answered, that is the conference I would like to have attended.

[1] http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-records-gallery/in-living-memory/in-living-memory-exhibition

‘You give me fever’

Archive machines project 2000-2010

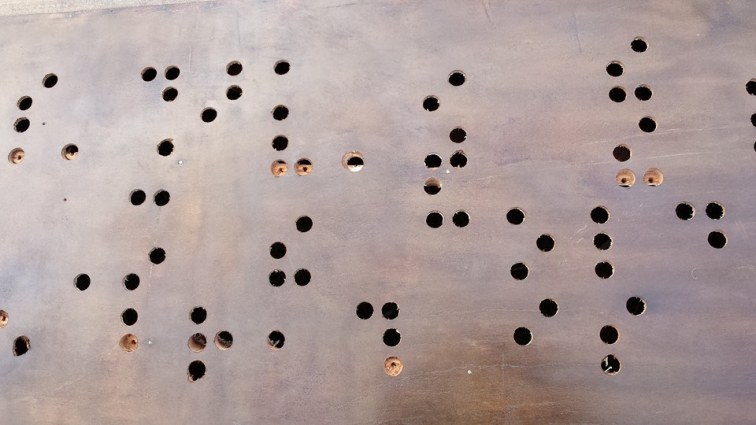

Steel, a material at once industrial, architectural, and automotive, dates very quickly. Whether in its pristine, raw state or in the artefacts of so many superseded modernities, it is stamped with the signs of its manufacture and its use value. It shines or rusts according to its mix or use. It takes the imprint of both its point of origin and its intended function. Then it wears out, wears away, weathers, needs replacing, resurfacing, taking its place in the narratives of time, consumption and, invariably, masculinity. Marked by the aura of both machine and functional object, it nonetheless still implies metal, oil and their transformation. Steel is alchemical and thus the repository of a nostalgia, of a certain inbuilt obsolescence, of a certain style. In this case the visual rhetoric of cars, consumption and money. These panels – petrol station signage – have a kind of history, beginning in industrial processes, and generating a certain cultural currency, a semiotic charge. In turn the rhetoric of unleaded, super, $, most credit cards implies spatial metaphors, and the logic of transaction and transition. Perhaps the petrol station is not unlike the mall or the airport, interstitial, geographically specific but culturally general, ubiquitous. A double-sided assemblage, they are re-marked: targets, tin men, toy soldiers, money and oil, Americana and automobiles, minimalist visual rhetoric, and signatures for abstraction, op and pop, the painterly gesture as impersonal and generalized (self) portrait, echoes of the grid, the mark as bodily habit, reflex, intuition. This material and significatory cascade creates a tear in social conventions, puts the viewer in my place, challenges the assumption of mastery and epistemological surety, and by implication, the subject/object relation: that’s archive fever.

Less talk, more action

on art, analysis and quasi-concepts

This is the introduction to a paper about theory/practice/praxis. A version was first presented at the Art Association of Australia Conference 2005 Sydney Australia

How can we think the heteromorph, we for whom the very notion of form is to shape matter into that which is single, unified, and identical to itself? What would it mean to worship not that which is self-same, but that which is self-different? To our way of thought, derived as it is from a tradition of monism, matter cannot be conceived distinct from form, because matter has already been caught up in a ‘systematic abstraction’. It has been constructed within a relationship of two verbal entities; abstract God (or simply Idea) and abstract matter, the prison keeper and the prison walls. Matter, thought through this ‘metaphysical scaffolding’, is never base. Base materialism … begins with the heterological thought of nonidentity.

Rosalind Krauss The Optical Unconscious

…matter is heterogenous; it is what cannot be tamed by any concept.

Yve-Alain Bois Formless: a user’s guide

This paper is a conceptual experiment in transposing the traditional hierarchy between theory or discourse, and praxis, in order to reevaluate the legislative and legitimating authority of discourse on one hand; and the very nature of art practice on the other. In it I propose that through this transposition of conventional understandings of text, image and aesthetics we can unpack the consequences of the naturalised conflation of an experience of the artwork with the reading of an image.

What is at stake in the map of ideas I am about to draw then, is the epistemological value of art practices as understood through the materiality of their existence, and in ways always resistant to the discourses that attempt to account for them. At the core of this analysis is the premise that art – art objects and art making – is a complex, nuanced epistemology comparable to but distinct from any other: a system of knowledge or understanding, in many ways commensurable with but distinct from philosophy.

I will suggest that as the visual art object takes its place in image-saturated culture, we must begin to consider art a path to and through a metaphysics. In this sense my paper is about material forms, conceptual and contextual production and the discursive framing of objects and praxes; and the relationships between art and metaphor, language, poetry. In the space of and between translation into discourse, and in the material that cannot cross languages, forms, dialects. To quote Derrida on translation:

Translation, a system of translation, is possible only if a permanent code allows a substitution or transformation of signifiers while retaining the same signified, always present despite the absence of any specific signifier. This fundamental possibility of substitution would thus be implied by the coupled concepts signifier/signified, and would consequently be implied by the concept of the sign itself. Even if … we envisage the distinction between the signified and the signifier as the two sides of a sheet of paper, nothing is changed. Originary writing, if there is one, must produce the space and the materiality of the sheet itself.

For Derrida, in his compelling analysis of writing in the general sense, and of the generative power (and violence) of this writing, this is the space of the sheet of paper. I want to understand these ideas in terms of materiality in all the broader sense: what it is in the art object that cannot be assimilated in the totality of its image, nor in the analysis of its signs. To discuss this proposition I will draw some critical parallels between discourses of subject/object, space/time, inside/outside, and matter/form: and their impact on notions of meaning and mastery.

The substance of this proposal is to examine what takes place alongside what we take for knowledge, if by knowledge we mean the conventions and assumptions of an epistemological project that has meaning as its outcome or product.

Deleuze’s fold; the idea of the formless as it pertains to matter and in relation to the aesthetic field; and the psychoanalytic formulation of resistance seem to me to demonstrate productive tensions that allow me to forge intersections between the physical, metaphysical and psychological orders of events and objects.